What is the Doughnut economy and why does it matter?

“The Doughnut offers a vision of what it means for humanity to thrive in the 21st century – and Doughnut Economics explores the mindset and ways of thinking needed to get us there.”

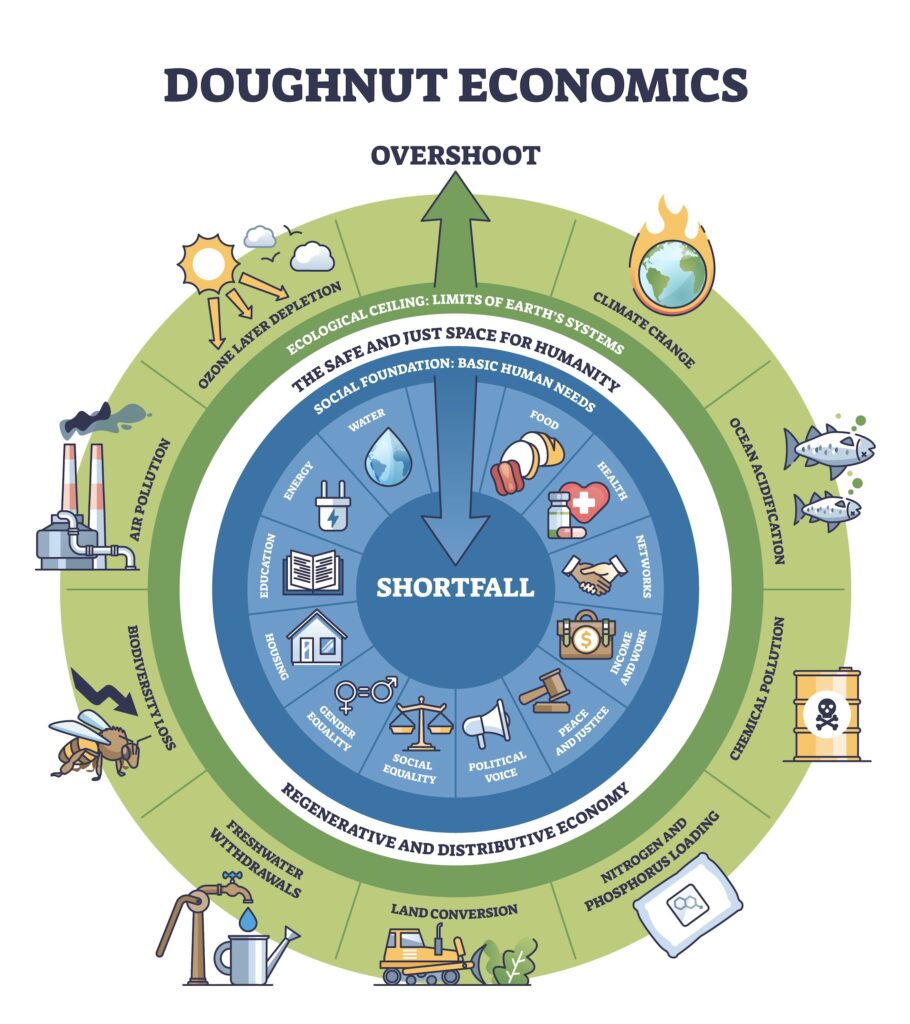

The concept of a Doughnut economy was developed by University of Oxford economist Kate Raworth in a 2012 paper for Oxfam entitled “A Safe and Just Space for Humanity”. It sought to offer a visual representation of a fair and sustainable economic system, creating a space between planetary and social boundaries within which humanity could thrive.

The paper laid out a simple premise: “Achieving sustainable development means ensuring that all people have the resources needed – such as food, water, healthcare, and energy – to fulfil their human rights. And it means ensuring that humanity’s use of natural resources does not stress critical Earth system processes, by causing climate change or biodiversity loss, for example, to the point that Earth is pushed out of the stable state, known as the Holocene, which has been so beneficial to humankind over the past 10,000 years.”

The inner circle of the doughnut ring is the social foundation for the planet. Beneath it, in the central hole, are life’s essential elements, to which many people lack access. These areas were inspired by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, and include healthcare, education, social equity, water, food, gender equality, a political voice, peace and justice, income and work, networks, housing and energy.

The crust represents the environmental ceilings or planetary boundaries on which life depends. If these boundaries are breached, the doughnut has damaging consequences beyond its outer edge, including unpalatable environmental damage such as ozone layer depletion, climate change, ocean acidification, chemical pollution and biodiversity loss.

Environmental damage and social challenges

The Doughnut model is an ideal, but getting there is a significant challenge. It is already clear that humanity is exceeding the planet’s boundaries, and many damaging environmental changes are starting to take place. At the same time, many people are living below the social foundation: nearly half the world’s population lives in poverty (defined as an income of less than $2.15 per day according to World Bank in 2022). Many lack access to proper nutrition, clean drinking water and adequate health services, according to the United Nations.

Raworth concluded in 2012 that providing the additional calories needed by the 13% of the world’s population suffering from hunger would require just 1% of the current global food supply.

The problems are often allocation rather than scarcity of resources. Raworth’s original report for Oxfam concluded that providing the additional calories needed by the 13% of the world’s population suffering from hunger would require just 1% of the current global food supply.

It is a similar picture for energy. Bringing electricity to the 19% of the world’s population who currently lack it could be achieved with an increase of less than a 1% in worldwide carbon emissions, while ending income poverty would entail just 0.2% of global income.

The problem, Raworth says, is that “moving into this space demands far greater equity – within and between countries – in the use of natural resources, and far greater efficiency in transforming those resources to meet human needs”. In other words, countries need to work together to achieve a fairer allocation of resources. Given how difficult it has been to forge agreement on an issue as crucial as curbing global warming, this is a tough task.

Excessive consumption of resources

It is the richest countries that would need to make the biggest adjustment to their behaviour. Excessive consumption of resources and the production patterns of the companies producing goods and services for the wealthiest 10% of the world’s population are a major source of planetary stress. In every area of consumption – carbon, nitrogen, food – the world’s wealthiest countries take the lion’s share.

Raworth adds: “Moving into the safe and just space for humanity means eradicating poverty to bring everyone above the social foundation, and reducing global resource use to bring it back within planetary boundaries. Social justice demands that this double objective be achieved through far greater global equity in the use of natural resources, with the greatest reductions coming from the world’s richest consumers.”

The Doughnut economy is compatible with the circular economy which aims to decouple economic growth from the consumption of finite resources.

The Doughnut economy is compatible with the circular economy, a concept designed to minimise waste and maximise resources efficiency by making the end of a product’s life part of its initial design, and which aims to decouple economic growth from the consumption of finite resources.

In a true circular economy, there is no waste – the system emphasises regeneration and restoration. The Doughnut economy concept is broader, and takes into account both the social and environmental dimensions of sustainability. This makes the circular economy a tool that works toward bringing the doughnut economy to fruition.

Barriers to progress

There are plenty of barriers to achieving a doughnut economy, not least that it requires redistribution of resources and a rethinking of how economic progress is measured. For example, the current measure – growth in gross domestic product – is an inadequate metric for areas such as poverty reduction.

Political will is limited, particularly as geopolitical conflict preoccupies leaders of the world’s biggest and most powerful countries, and the international collaboration required to achieve these goals is in short supply. Nevertheless, the concept has received endorsement from influential global figures as well as organisations such as the World Economic Forum and the United Nations.

In the UK, a Doughnut Economics Action Lab has been seeking to implement Doughnut economy initiatives at a grass-roots level, involving working with education practitioners, local governments, cities and regions as well as businesses. Supported by the National Lottery Community Fund, the initiative claims some success in “helping policymakers think differently, look at economic narratives differently, and make decisions differently”. It hopes to build an ‘ecosystem of changemakers’ – a movement created from the bottom up, rather than from the top down.

For the time being, the Doughnut economy remains an ideal rather than reality. However, looking at economic progress in new ways may become increasingly important as the world’s limited resources are increasingly drained.

Mortgage

Mortgage Personal loan

Personal loan Savings

Savings