Derivatives: options and futures

There are certain instruments you can invest in whose value is derived from the price of another asset or set of assets underlying them. These instruments are known as “derivatives”. Today, myLIFE tells you what they’re all about, including how they work and the difference between two specific types of derivative contract: options and futures.

Before we go into detail, let us make one thing very clear: however attractive they may seem, derivatives are not without their risks. If you’re considering investing in products like these, we strongly recommend you first read the accompanying documentation and talk to your banker in order to find the ones most suitable for your investor profile.

In essence, a derivative is a contract between two or more parties that sets out conditions for future cash flows, generally depending on the change in price of an underlying asset or set of assets. It’s important to understand that the underlying asset is not physically traded at the moment the contract is signed. This trade could be optional (as with options), may take place at a future date (futures) or may never be intended to happen at all (interest rate swaps, for example).

As indicated above, there are different types of derivatives that can be used to manage risk (known as hedging), or for speculation, including as part of arbitrage strategies or to achieve a leverage effect. Many different types of derivative exist for virtually any asset class, be it stocks, commodities, bonds or foreign currency trades. The main types of derivative are:

- futures

- forwards, a type of future traded over the counter rather than on an exchange

- options

- warrants

- swaps

In addition, although they aren’t derivatives themselves per se, structured products often have derivatives integrated within them.

For the most part, derivatives are complex instruments that often get a bad rap thanks to the infamous hedge funds that use them. Some of you may remember Long-Term Capital Management, the fund that teetered on the brink of bankruptcy in 1998, posing a dangerous threat to the whole financial system.

But using derivatives to hedge risk and improve returns has been around for generations. Now let’s take a closer look at two different types of derivative: futures and options.

Futures

Futures are standardised contracts traded on regulated markets. These financial products enable parties to commit to buying or selling an asset on predefined terms: they must agree on the quantity and price of the asset. In the vast majority of cases, counterparties to this type of contract never make any physical exchange of the underlying asset when the futures position is liquidated. All that changes hands is the difference between the price of the underlying asset listed on the contract and its real price at the time the contract expires.

Both parties have to pay something called the “initial margin” (a percentage of the total value of the contract) when the contract is signed. The value of the contract is set based on current market prices. Parties may have to add more funds to their accounts (known as a “margin call”) if a change in the market price of the underlying asset renders the initial margin smaller than a given maintenance margin, which is specified in the contract. Margin calls cover the difference between the settlement price on the day of the call and the one the day before. A party can close the position at any time before it expires by completing the purchase (or sale) of the asset on the terms initially agreed upon.

Futures are an important means of managing different types of risk, such as price, foreign exchange and interest rate risk.

Futures are an important means of managing different types of risk. Companies engaging in international trade use futures to manage foreign exchange risk, interest rate risk and price risk by fixing the buying or selling price of the commodities they use in advance. These include things like petrol, agricultural products or certain materials.

Futures increase the efficiency of the underlying market by helping reduce the extra costs associated with buying assets. For example, it’s much less expensive and more efficient to open a long position on the S&P 500 Futures index than to replicate the index by buying every stock on it. Furthermore, studies have shown that bringing futures into a market increases overall trade volumes in the underlying asset. That’s what makes futures risk hedging and management tools that help bring down transaction costs and increase liquidity.

Options

Options are contracts purchased for a premium that then give the holder (the party who bought the option) the right – but not the obligation – to buy or sell an asset on a specific date (European options), or by that date (American options). Investors generally use options when they don’t want to open a position in the underlying asset, but still want the opportunity to increase their exposure in the future if its price changes significantly. There are dozens of options with different strategies, but the most common are:

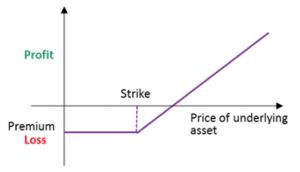

- Long call – You can buy an option giving you the right to purchase (call) and thus hold (long) an underlying asset at a future date for a fixed price, if you speculate that the market price of that asset will rise. The holder of a long call option will achieve a gain if, when the option is exercised, the market price of the asset is higher than the strike price listed in the option contract, plus the premium paid for it.

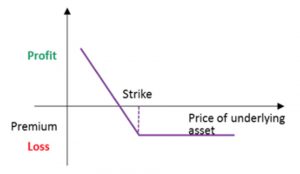

- Long Put – If you think the market price of an asset that you hold (long) is going to fall, you can buy an option giving you the right to sell it (put). The holder of a long put option will achieve a gain if, when the option is exercised, the market price of the asset is lower than the strike price set in the option contract, minus the premium paid for it.

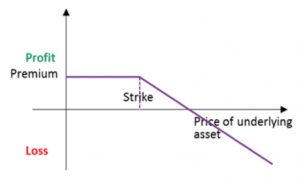

- Short Call – If you think a certain asset will fall in price, you might sell a call option on it to someone else. It is this counterparty who then decides whether to exercise the option. As the seller of the call option, your maximum gain is the premium the buyer paid for it (achieved if the price of the underlying indeed drops). But if the price of the underlying asset goes up, your potential losses are unlimited.

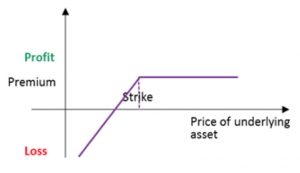

- Short Put – If you think an asset will increase in price, you can sell a put option on it. As the seller of the put, your maximum gain is the premium the buyer paid for it (achieved if the price does increase). However, if the price of the underlying asset drops, your losses may be substantial (but aren’t unlimited, as the lowest it could ever drop is zero).

Would you like to know more about different investment products? Check out our special “Guide to investing: asset classes”.

Mortgage

Mortgage Personal loan

Personal loan Savings

Savings