Hooked on a feeling – keeping emotions out of your investments

Most investors know what they shouldn’t do: they shouldn’t panic in the face of market volatility, buy the latest hyped stock, or invest in something they don’t understand. However, when it comes to money, it’s hard to prevent emotions from getting in the way.

The efficient market hypothesis much in favour in the 1960s and 1970s postulated that in aggregate, investors were completely rational, so the price of any given share or bond was a perfect reflection of all the information available about the company that issued it and the market and economic environment in which it was trading.

However, the efficient market theory is now widely disputed, not least by renowned investment strategists including Warren Buffett and George Soros. How can it explain a phenomenon such as the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s, or the way the collapse of the US sub-prime housing market boom brought down financial institutions all over the world. Investors, it seems, are clearly vulnerable to letting non-rational factors impinge on their efficient judgement – and not just individuals, but sober institutional investors that are presumed to know better.

Emotional factors can take many forms. An individual investor may be influenced by their friends, family or the media, and these days social media, allowing what they see, read and hear to guide their decision-making, rather than undertaking rational analysis.

They fall victim to the human tendency to use heuristics – mental short cuts – to make rapid judgements. They assess the success prospects of a particular company by noting that a certain shop is busy, or that they personally like a particular product, elevating an anecdotal and possibly irrelevant example into evidence presumed to be of scientific value.

Investors in tandem

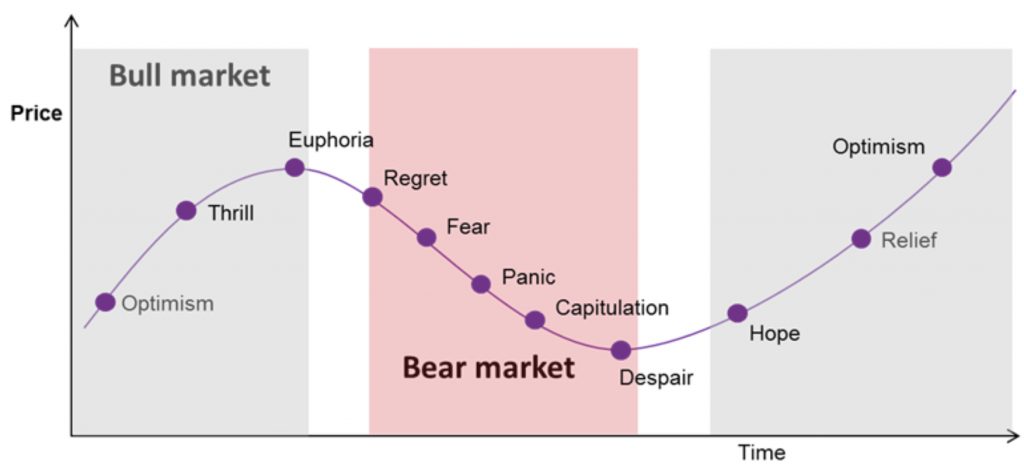

Another problem is that emotional investors are prone to move in tandem with the market as a whole, as individuals (and sometimes institutions, too) allow their own judgement to be clouded by the actions of everyone else. If there is widespread panic, they sell; if markets are euphoric, they buy. This means they are frequently buying or selling at the wrong moment.

According to US consultancy Dalbar, in 2023, the average American investor in equity funds received a return of 20.79%, compared with a gain of 26.29% for the S&P 500 index. This “investor gap” of 5.5% – the third largest in 10 years, and almost double the level in 2022, when investor returns fell by 21.17% while the index was down by 18.11% – was the price of not having the patience to ride out market fluctuations, according to Dalbar chief marketing officer Cory Clark.

Whether a particular year is extremely difficult for equity investment, like 2022, or a bountiful one, like 2023, Dalbar’s annual Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behaviour reports repeatedly indicate that investors consistently make poor timing decisions, driven by emotional factors that can be simplistically boiled down to fear and greed.

Over the 20-year period to September 2023, the S&P 500 averaged growth of 9.66% a year, but the typical US equity investor would be lucky to receive more than half of that; bond investors fare no better. A behavioural gap in performance is clearly visible.

Can one avoid being swayed by emotion?

Behavioural psychologist Paul Davies, who cites the work of Nobel Prize-winner Daniel Kahneman and his long-time collaborator Amos Tversky, says the evidence does not support the view that armed with all the information they need, people will behave rationally. The view that humans are computational – that if they have the right information, they will take the correct decisions – is flawed, he says.

The best way to make the right financial decisions is to ensure you make as few decisions as possible, because you are more likely to make wrong ones.

But simply knowing that such behavioural quirks exist is not enough to change them. Davies argues that people need to put processes in place to support rational behaviour, to make it easier to do the right thing. He also says the best way to make the right financial decisions is to ensure you make as few decisions as possible, because you are more likely to make wrong ones. The most damaging of all cognitive biases is “action bias” – the tendency to believe that value can only be realised through constant action.

What does this mean in practice? Regular savings fed automatically by standing orders from your account are an obvious example. If you need to make a conscious decision to invest each month, it becomes complicated. You will be called on to decide repeatedly whether there are more important priorities each month for your money than the nebulous concept of your ‘future’. In all likelihood there will often, perhaps always, be some more attractive or pressing priority.

Contingency rules

You are also bound to look at the level and direction of the market, trying to calculate whether it is a good or bad time to buy. If the money leaves your account and is invested immediately, some months you will win and some you will lose, but given that markets tend to go up over the long term, you are likely to benefit in the end, in addition to avoiding all the agonising and time-consuming decision-making.

Davies also suggests building personal ‘if then’ statements into financial planning. This allows you to decide ahead of time what your course of action would be if, for example, the stock market were to drop by 10%. This can help guard against taking emotionally-influenced decisions on the spur of the moment, by putting contingency rules in place.

Financial advisers often determine levels of ‘highest acceptable loss’ with clients. Establishing their maximum loss tolerance is useful not only as mental preparation for the certainty that at some point they will experience losses, but also as a way to programme investment strategy away from day-to-day market developments.

Automatic rebalancing

Similar rules should apply to asset allocation decisions. In general, most investors work with a strategic asset allocation – their long-term positioning, geared to achieve their ultimate financial goals. This will determine broadly how much of their portfolio they hold in equities, bonds and other types of asset, such as real estate. Tactical asset allocation, by contrast, is a means of adjustment to changing market conditions.

The key is to keep your eye on the strategic blueprint, rather than being swayed by tactical choices. The best way is through automatic rebalancing, in which the portfolio is systematically adjusted to maintain the original asset allocation. This also takes away the need for decision-making or concern about whether it is the right time to buy into a particular market. Under automatic rebalancing, investors move money out of expensive markets that have done well, and into cheaper assets that have done less well.

Of course, short-term opportunities may arise that can be exploited, and adjusting one’s portfolio tactically may be worthwhile at times, especially if a particular market appears to be over-reliant on the performance of a small number of individual stocks (like, in recent years, big technology groups). However, in general it is better to decide on an asset allocation strategy and stick with it, conducting reviews at regular intervals, rather than rethinking everything when a market shock arises.

Understanding one’s limitations

More difficult to do, but still important, is to understand one’s own limitations. Overconfidence in your decision-making, a reluctance to accept that a situation has changed, and high turnover stemming from frequent changes of mind are all likely to have a negative impact on long-term portfolio returns.

Investors frequently have inflated expectations of the potential returns from their investments, which leads to a poor appreciation of the risks involved. This can also be addressed by building structural checks and balances into the investment process. Reflecting on the outcome of past investment decisions can also be beneficial: What went well, and what did not? Are there any conclusions to draw?

It is easy to be emotional about money, but it is generally a recipe for poor decision-making. The best policy is to construct an investment strategy approach that keeps decision-making to a minimum, and reduces the potential for emotion that can lead investors into error.

Mortgage

Mortgage Personal loan

Personal loan Savings

Savings