Investments: a few true stories that are worth thinking about

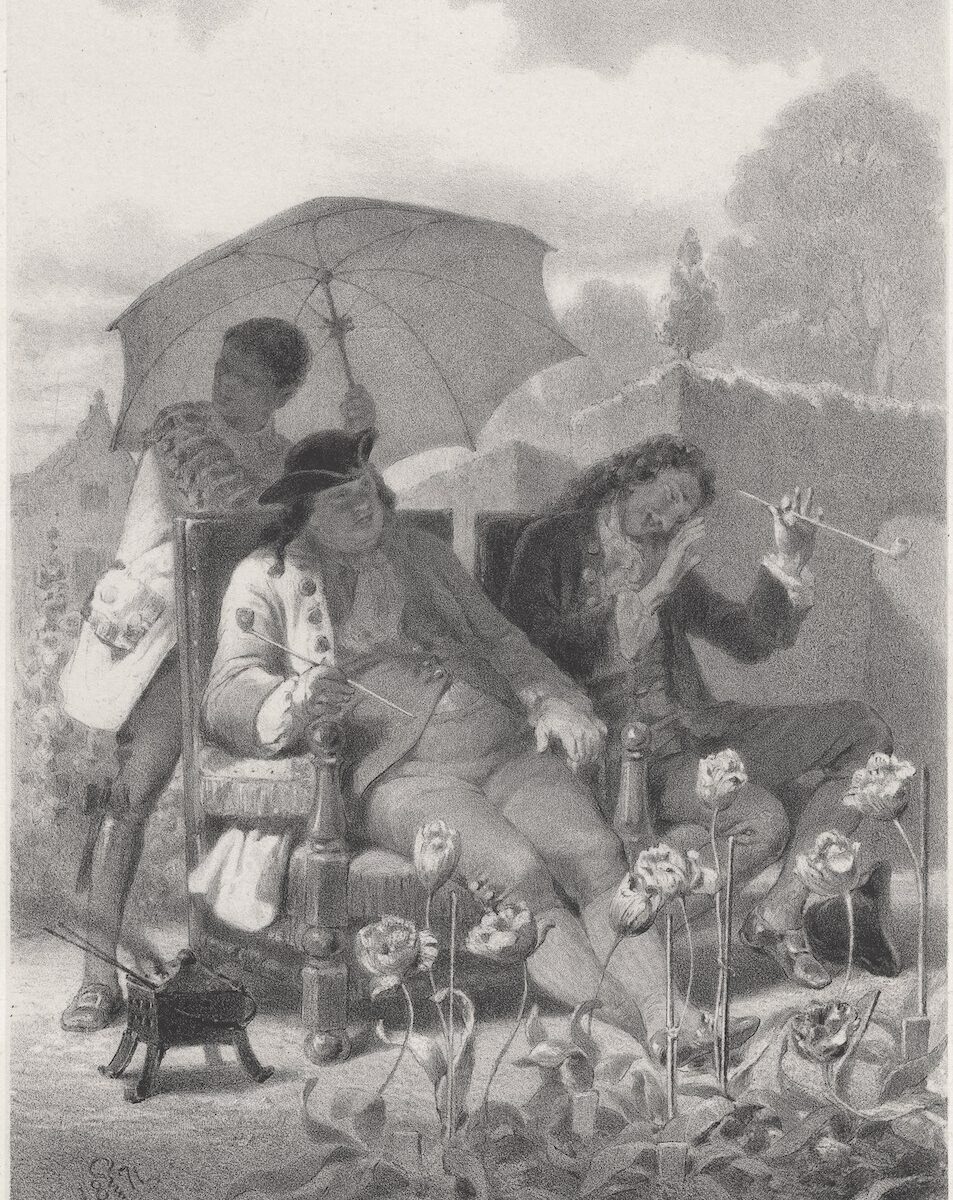

Tulip mania in the seventeenth century, an unforgettable evening in Monte Carlo in 1913, or a narrow escape in New Orleans in 2004 – myriad anecdotes offer valuable advice for anyone hoping to make better decisions, particularly on financial issues. myLIFE has chosen two of these anecdotes to illustrate how cognitive bias affects our financial decisions.

Don’t be fooled by your own story!

We all love a good story, whether it’s a fairy tale, great epic saga, Hollywood blockbuster or the success story of a famous entrepreneur. Have you ever asked yourself why this is, or why the “story” format is so popular on social media? For one simple reason: stories give meaning to the world around us.

Our brains are story-telling machines which help us to better understand our environment. Each one of us is a budding scriptwriter! And linking together several elements and events to create a storyline allows us to find meaning. Without this, we would be confronted with an environment where, all too often, chance, confusion and chaos seem to rule.

Sometimes, we use all of the elements to make up a story that suits us. This can have damaging consequences.

Most of us don’t like chance, risk or, worse still, uncertainty. So we try to reassure ourselves, and maintain some semblance of control over what’s happening to us. We structure our days with a routine, we organise our weekend activities based on the weather forecast, and we rely on specialist research to organise our finances. That’s all well and good when we base our scenario on objective elements. Sometimes, we use all of the elements to make up a story that suits us. This can have damaging consequences.

With this series of articles about finance and behavioural economics, myLIFE has shown you that we should mistrust cognitive bias that leads us to mistake fiction for reality and clouds our investment decisions. Today, we would like to tell you two true stories that illustrate the potential damage that our cognitive bias can have on our finances and much more.

Story 1: the Monte Carlo fallacy

The story takes place on 18 August 1913, at a roulette table in the Monte Carlo Casino. After the roulette ball landing on black several times in a row, several players bet increasingly large amounts on red, believing that probability dictated that the ball would soon land there. But only after the ball had landed on black 26 consecutive times did the run end and the ball finally landed on red. As a result, players lost enormous sums and the casino filled its coffers on this unusual evening that gave its name to the phenomenon of the gambler’s fallacy, or the Monte Carlo fallacy. What happened?

The gambler’s fallacy describes our (false) conviction that the future probability of a random event is influenced by the previous outcomes for the same type of event. In other words, we create a false causal link between random events in the past and random events in the future. This link is false because random events are not influenced by what happened before them. For example, the probability of heads or tails is 50/50 every time you toss a coin, even if heads won the previous 3, 10 or 100 times.

Random events are not influenced by what happened before them!

How can we avoid such sophistry? By ensuring that we do not see causality where none exists. This is true in all areas, including investment. The Monte Carlo fallacy plays a particularly important role in financial analysis. Economists Hersh Shefrin and Meir Statman thus illustrated that investors tend to hold onto shares that have fallen, and to sell those that have risen.

Some investors come to the startling conclusion that the continued rise in the price of a share means that it will soon collapse, and often decide to sell prematurely. Conversely, holders of shares that have lost in value tend to believe that these will recover, and hold onto them while continuously losing money on them. A great variety of factors influence changes in the price of a share, and as the famous phrase would have it: past performance is no guarantee of future performance.

It is therefore naive and dangerous to base our decisions solely on what we believe is a pattern. This error can also be seen among investors who believe that their previous successes are a reliable indicator of their future investment success.

The moral of the story: be wary of overconfidence! It is always dangerous to think that the past determines the future. You should take full stock of your investments in order to identify any real signals and avoid relying on your supposed intuition or illusory lucky touch. Take the advice of experts rather than writing your own script and seeing causality where none exists.

Story 2: the Superdome, or the Ostrich policy

Our second story takes place in New Orleans in 2004. The local authorities are warned of the approach of the devastating Hurricane Ivan, and that the dilapidated levees around the city will not protect the low-lying areas of the agglomeration in the event of flooding. 100,000 people could find themselves trapped. An emergency plan is set up to evacuate families to the city’s Superdome stadium. Those in charge of the site immediately issue a warning that they will be unable to accommodate everyone who needs evacuating. Luckily, the 2004 hurricane changed course after hitting the Caribbean and missed New Orleans. Everyone heaved a huge sigh of relief and carried on with everyday life; no work was done on strengthening the city’s levees or creating a workable evacuation plan.

One year later, catastrophe struck with Hurricane Katrina. The Superdome was indeed unable to accommodate all those in distress, the levees burst at over 50 different locations and over 1,500 people lost their lives. This crisis illustrates the Ostrich syndrome, of hiding our heads in the sand to avoid seeing the danger. In New Orleans, there was not a failure of forecasting, but an inability to take the decisions required to deal with an identified risk.

It is not unusual to take the wrong decisions, or to refuse to take decisions when faced with foreseeable catastrophes or serious events.

It goes without saying, that this can happen in other circumstances in our lives. At an individual or institutional level, it is not unusual to take the wrong decisions, or to refuse to take decisions when faced with foreseeable catastrophes or serious events. Why? Because the exceptional nature of these events strengthens our normality bias, which makes us believe that everything will sort itself out and revert to normal. We refuse to imagine that a virus in China could bring the entire world to a halt for months, or that the great plan on which we have bet our savings has serious holes in it.

The story of New Orleans also illustrates another aspect known as amnesia bias. Many people took out flood insurance after witnessing the tragedy of Hurricane Katrina. Yet within barely three years, demand for flood insurance had fallen to pre-Katrina levels. This bias is a method of cognitive protection that tends to make us forget the pain associated with events such as a natural catastrophe or previous financial crisis. The memory remains, but the impact is no longer visceral.

We also see ostrich behaviour when it comes to taking financial decisions. The economist George Loewenstein defines this as people using their intelligence to reinforce their beliefs rather than looking for the truth, by developing strategies that aim to avoid information that contradicts our beliefs. The economist and his colleagues studied movements on over a million retirement savings accounts between 2007 and 2008 and successfully identified ostrich behaviour with regards to financial issues. This consisted of investors being less likely to connect to accounts on the day after market setbacks, although they would have been well-advised to study their personal investment situation in light of this general movement. In contrast, ostrich behaviour meant investors connected to their accounts more often and on repeated occasions at the weekend if the market had closed up or to their advantage, even though markets were closed and there was therefore nothing in particular to check on!

Ostrich behaviour is not the preserve of small, novice investors – on the contrary! According to Loewenstein, the bigger the investment portfolio of an individual, the higher the likelihood of ostrich behaviour. Consider yourself warned!

The bigger the investment portfolio of an individual, the higher the likelihood of ostrich behaviour.

The moral of the story: don’t bury your head in the sand! Avoiding your problems will not keep out danger or loss. Hope for the best and prepare for the worst rather than refusing to look reality in the face. Also, bear in mind that you shouldn’t cancel insurance policies on the pretext that you haven’t needed them for a long time. Insurance is of no use until the day the accident actually occurs! And then not having insurance could have dramatic consequences.

Mortgage

Mortgage Personal loan

Personal loan Savings

Savings